Appendix B — Methods

B.1 Overview

This document provides a detailed explanation of the methods and steps used to construct the models and test the thesis hypothesis.

For an in-depth discussion of the thesis question and hypothesis, see Supplementary Material A.

B.2 Approach and Procedure Method

This study employed the hypothetical-deductive method, also known as the method of conjecture and refutation (Popper, 1972/1979, p. 164), as its problem-solving approach. Procedurally, it applied an enhanced version of Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST), grounded on the original ideas of Neyman-Pearson framework for data testing (Neyman & Pearson, 1928a, 1928b; Perezgonzalez, 2015).

B.3 Measurement Instrument

Chronotypes were assessed using the standard version of the standard Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ) (Roenneberg et al., 2003), a well-validated and widely applied self-report tool for measuring sleep-wake cycles and chronotypes (Roenneberg et al., 2019).

The MCTQ captures chronotype as a biological circadian phenotype, determined by the midpoint of sleep (MS) on work-free days (MSF), accounting for any potential sleep compensation due to sleep deficits (sc = sleep correction) on workdays (Final abbreviation: MSFsc) (Figure B.1) (Roenneberg, 2012).

BT = Local time of going to bed. SPrep = Local time of preparing to sleep. SLat = Sleep latency (Duration. Time to fall asleep after preparing to sleep). SO = Local time of sleep onset. SD = Sleep duration. MS = Local time of mid-sleep. SE = Local time of sleep end. Alarm = Indicates whether the respondent uses an alarm clock. SI = “Sleep inertia” (Duration. Despite the name, this variable represents the time the respondent takes to get up after sleep end). GU = Local time of getting out of bed. TBT = Total time in bed.

Source: Created by the author.

Participants completed an online questionnaire, which included the MCTQ as well as sociodemographic (e.g., age, sex), geographic (e.g., full residential address), anthropometric (e.g., weight, height), and data on work and study routines. A version of the questionnaire, stored independently by the Internet Archive organization, can be viewed at: https://web.archive.org/web/20171018043514/each.usp.br/gipso/mctq

B.4 Sample

The analysis dataset consisted of \(65,824\) participants aged 18 or older residing in the UTC-3 timezone. These individuals completed the survey during a one-week period from October 15th to 21st, 2017, providing a snapshot of the population at that specific time.

The unfiltered valid sample included \(115,166\) participants from all Brazilian states. The raw dataset contained \(120,265\) individuals, with \(98.173\%\) of the responses collected between October 15th and 21st, 2017. This data collection period coincided with the promotion of the online questionnaire via a broadcast on a nationally televised Sunday show in Brazil (Figure B.2) (Rede Globo, 2017).

Source: Reproduced from Rede Globo (2017).

Based on 2017 data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’s (IBGE) Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNAD Contínua) (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, n.d.), Brazil had \(51.919\%\) of females and \(48.081\%\) of males with an age equal to or greater than 18 years old. The sample is skewed for female subjects, with \(66.433\%\) of females and \(33.567\%\) of male subjects. The mean age was \(32.109\) (\(\text{SD} = 9.258\)), ranging from \(18\) to \(58.95\) years.

To balance the sample, weights were incorporated into the models. These weights were calculated through cell weighting, using sex, age group, and state of residence as references, based on population estimates from IBGE for the same year as the sample. This procedure can be found on Supplementary Material D.

A survey conducted in 2019 by IBGE (2021) found that \(82.17\%\) of Brazilian households had access to an internet connection. Therefore, this sample is likely to have a good representation of Brazil’s population.

The sample latitudinal range is \(33.85°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -33.522°\), \(\text{Max.} = 0.329°\)) with a longitudinal span of \(22.741°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -57.553°\), \(\text{Max.} = -34.812°\)). For comparison, Brazil has a latitudinal range of \(39.023°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -33.751°\); \(\text{Max.} = 5.272°\)) and a longitudinal span of \(45.155°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -73.99°\); \(\text{Max.} = -28.836°\)), according to data from IBGE collected via the geobr R package (R. H. M. Pereira & Goncalves, n.d.).

Additional details about the sample can be found on Supplementary Material C.

B.4.1 Power Analysis

To evaluate whether the sample size was sufficient to detect effects meeting the Minimum Effect Size (MES) threshold (\(f^2 = 0.02\)), a power analysis was performed using the pwrss R package (Bulus, n.d.). The analysis determined that a minimum of \(1,895\) observations per variable was required to achieve a power (\(1 - \beta\)) of \(0.99\) at a significance level (\(\alpha\)) of \(0.01\). With a sample size of \(n = 65,824\), this study exceeds the required threshold, ensuring sufficient statistical power.

Further details on the power analysis are provided in Supplementary Material E.

B.5 Geographical Data

Geographic data were collected using the variables country, state, municipality, and postal code. These values were manually inspected and adjusted using lookup tables. The municipality values were initially matched using string distance algorithms from the stringdist R package (van der Loo, n.d.) and data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) via the geobr R package (R. H. M. Pereira & Goncalves, n.d.). Subsequent adjustments were performed manually to ensure accuracy.

This was a hard task involving crossing information from different sources, such as the QualoCEP (Qual o CEP, 2024), Google Geocoding (Google, n.d.), ViaCEP (ViaCEP, n.d.), and OpenStreetMap (OpenStreetMap contributors, n.d.) databases, along with the Brazilian postal service (Correios) postal code documentation. Hence, the data matching shown in the lookup table was gathered considering not only one variable, but the whole set of geographical information provided by the respondent.

All values were thoroughly checked for ambiguities, including municipality names. For instance, the name Aracoiba could refer to Aracoiaba in the state of Ceará or Araçoiaba da Serra in the state of São Paulo. Any values with potential matches to multiple municipalities were manually inspected to ensure accuracy and avoid errors.

B.5.1 Postal Codes

After removing all non-numeric characters from the Brazilian postal codes (Código de Endereçamento Postal (CEP)), they were processed by the following rules:

- Postal codes with 9 or more digits were truncated to the first 8 digits, as these represent the valid postal code.

- Postal codes with 5 to 7 digits were padded with trailing \(0\)s to reach 8 digits.

- Postal codes with fewer than 5 digits were deemed invalid and discarded.

After this process, the postal codes were matched with the QualoCEP database (Qual o CEP, 2024). Existing postal codes were than validated by the following rules:

- If the postal code had not been modified and the state or the municipality was the same, it was considered valid.

- If the postal code had been modified and the state and municipality were the same, it was considered valid.

- Else, it was considered invalid.

As a final attempt, invalid postal codes were matched using geocoding data obtained from the Google Geocoding API (Google, n.d.) via the tidygeocoder R package (Cambon et al., 2021). The same validation process above was then applied to these results. This approach successfully reduced the number of invalid postal codes from 563 to 292, achieving a 48.13% reduction. Postal codes that remained invalid after this process were excluded from the final dataset.

It’s important to note that some postal codes could not be evaluated because they were missing the state or municipality information. These postal codes were maintained, but no geocode data was associated with them.

Finally, the state and municipality variables were adjusted using the data from the valid postal codes.

Non-Brazilian postal codes were not validated but were cleaned by removing non-digit characters and excluding codes with three or fewer digits. Additionally, they underwent a data cleaning process through manual visual inspection.

B.5.2 Latitudes and Longitudes

Latitudes and longitudes were determined based on the municipality and postal_code variables. These coordinates were primarily sourced from the QualoCEP database, which integrates geocoding results obtained via the Google Geocoding API. For a detailed comparison of latitude and longitude values between the QualoCEP database and the Google Geocoding API, refer to Supplementary Material I.

For cases without a match in the QualoCEP database, the Google Geocoding API was utilized via the tidygeocoder R package. For respondents missing valid postal codes, latitude, or longitude were then approximated using the average coordinates of their municipality as recorded in the QualoCEP database. These cases represented a minimal proportion of the total dataset (\(0.418\%\)).

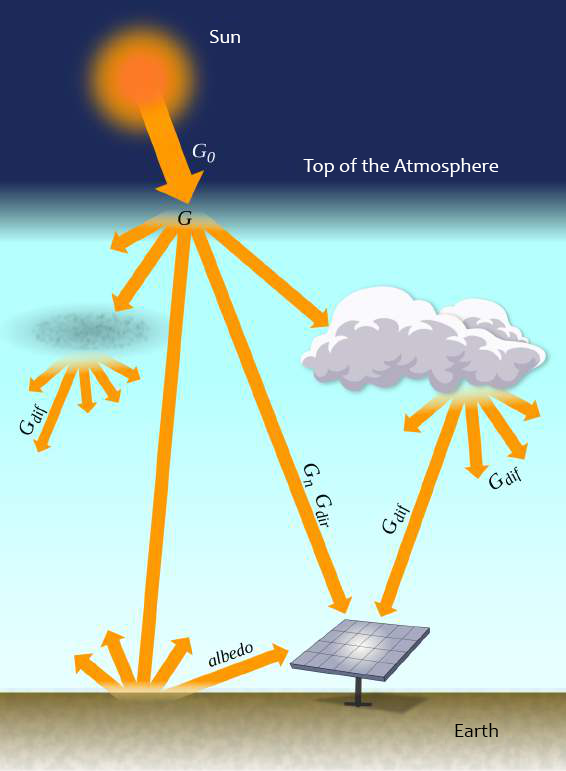

B.6 Solar Irradiance Data

The solar irradiance data used in this study originates from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) 2017 Laboratory of Modeling and Studies of Renewable Energy Resources (LABREN) Solar Energy Atlas (E. B. Pereira et al., 2017). Specifically, the Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) data was utilized, representing the total amount of solar irradiance received by a horizontal surface on the ground.

The dataset includes annual and monthly averages of daily total irradiation in Wh/m².day, with a spatial resolution of 0.1° x 0.1° (approximately 10 km x 10 km). Notably, the radiance data corresponds to the same year in which the sample was collected, ensuring temporal alignment between the irradiance measurements and the study data.

\(G_{0}\) = Extraterrestrial irradiance. \(G_{n}\) = Direct normal irradiance. \(G_{dif}\) = Diffuse horizontal irradiance. \(G_{dir}\) = Direct horizontal irradiance. \(G\) = Global horizontal irradiance. \(G_{i}\) = Inclined plane irradiance.

Source: Adapted by the author from E. B. Pereira et al. (2017).

B.7 Astronomical Calculations

The suntools R package (Bivand & Luque, n.d.) was used to compute sunrise, sunset times, and daylight duration for each participant’s location. These calculations are based on the algorithms provided by Meeus (1991) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Dates and times for equinoxes and solstices were sourced from the Time and Date AS service (Time and Date AS, n.d.). To ensure accuracy, this data was cross-verified with calculations from Meeus (1991) and results from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) ModelE AR5 Simulations (National Aeronautics and Space Administration & Goddard Institute for Space Studies, n.d.).

B.8 Data Management

A data management plan for this study was created and published using the California Digital Library’s DMP Tool (Vartanian, 2024). It is available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3JZ7K

All data are securely stored in the study’s research compendium on the Open Science Framework (OSF), hosted on Google Cloud servers in the USA. The data are encrypted using a 4096-bit RSA key pair (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) and a unique 32-byte project password to ensure confidentiality.

Access to the data requires prior authorization from the author on the Open Science Framework (OSF) and the installation of the corresponding encryption keys.

B.9 Data Munging

Data munging and analysis followed the data science workflow outlined by Wickham et al. (2023), as illustrated in Figure B.4. All processes were conducted using the R programming language (R Core Team, n.d.) and several R packages. The tidyverse and the rOpenSci peer-reviewed package ecosystem and other R packages adherents of the tidy tools manifesto (Wickham, 2023) were prioritized.

Source: Reproduced from Wickham et al. (2023).

The MCTQ data was analyzed using the mctq R package (Vartanian, n.d.), which is part of the rOpenSci peer-reviewed ecosystem.

All processes were designed to ensure result reproducibility and adherence to the FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) (Wilkinson et al., 2016). All analyses are fully reproducible and were conducted using Quarto computational notebooks. The renv R package (Ushey & Wickham, n.d.) was employed to ensure that the R analysis environment can be reliably restored.

B.9.1 Pipeline

The data processing pipeline follows the framework described in the targets R package manual. It is fully reproducible and can be executed using the _targets.R file, located in the root directory of the thesis code repository.

B.9.2 Lookup Tables

Alongside the data cleaning procedures described in the pipeline, lookup tables were utilized to standardize text and character variables. These tables were manually curated by inspecting the unique values in the raw data and addressing common issues such as misspellings, synonyms, and other inconsistencies. The lookup tables are securely stored in the research compendium of this thesis.

The following text/character variables were cleaned using these tables: track, names, email, country, state, municipality, postalcode, sleep_drugs_which, sleep_disorder_which, and medication_which.

Due to the sensitive nature of the information, the lookup tables have been encrypted. They are accessible within the research compendium under appropriate authorization.

It is important to note that the matching process for the variables sleep_drugs_which, sleep_disorder_which, and medication_which remains incomplete. While these variables were not included in the analysis, they are available in the research compendium for reference.

For additional details about the matching process, particularly for geographical information, refer to the section on geographical data.

B.9.3 Circular Statistics

MCTQ relies on local time data, which are inherently circular (i.e., they repeat every 24 hours). Analyzing such variables poses unique challenges, as the calculated values can vary depending on the chosen arc or interval of the circle.

For instance, the distance between 23:00 and 01:00 can be interpreted as either 2 hours or 22 hours, depending on the direction of measurement. Therefore, the analysis must consistently define a direction to ensure accurate and meaningful results (Figure B.5).

- <--- h ---> +

origin

. . . 0 . . .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

18 6

. .

. .

. .

. .

. .

. . . 12 . . .

18 + 6 = 0hSource: Created by the author.

The analysis addressed this issue by adapting the values using 12:00 as a reference point. This method is particularly suitable for sleep data.

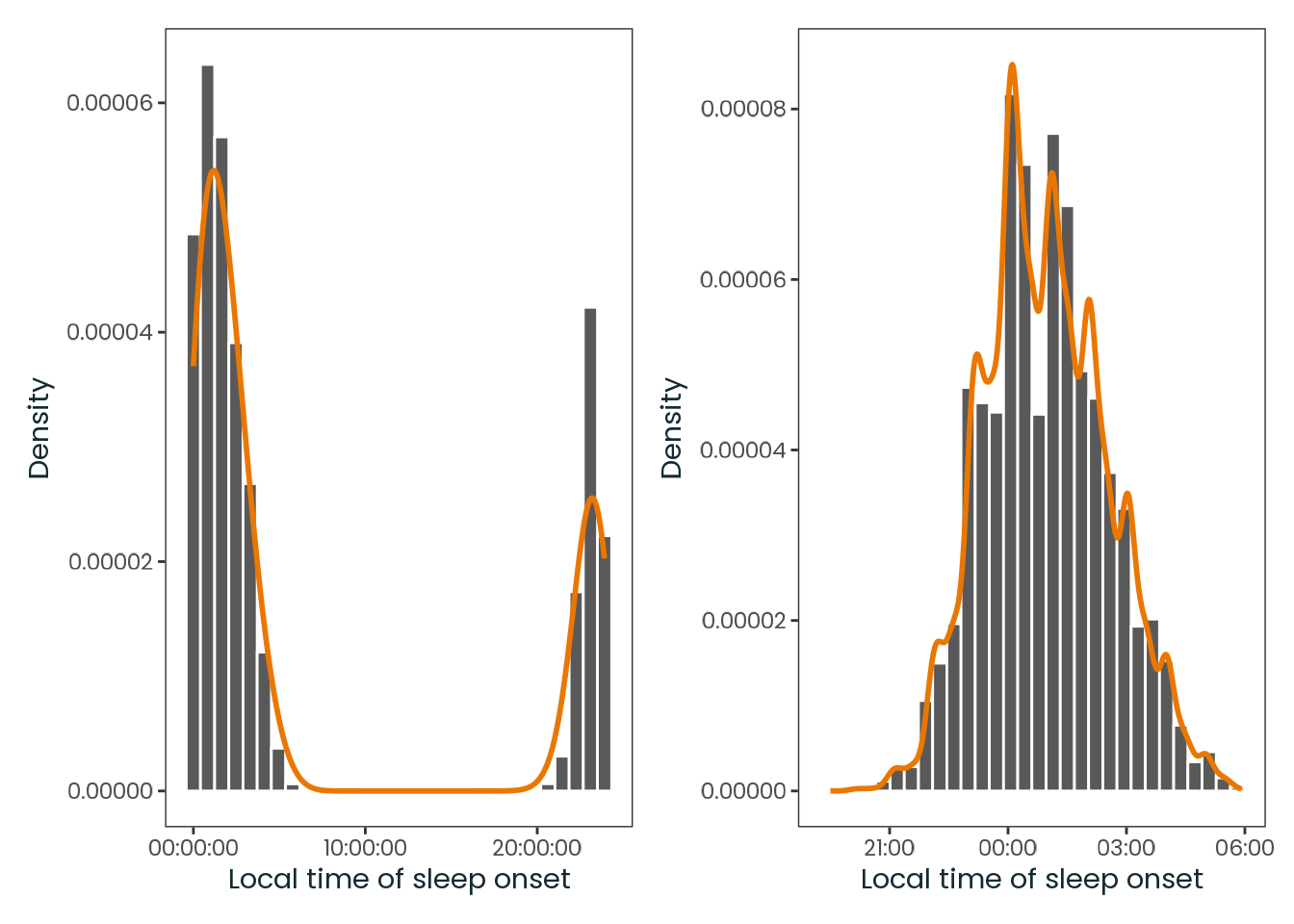

For instance, consider the local time of sleep onset. Some participants begin sleeping before midnight, while others do so after midnight. In this context, the shorter circular arc/interval (Figure B.6) is used, as most individuals typically do not sleep during the daytime or for durations exceeding 12 hours.

day 1 day 2

x y x y

06:00 22:00 06:00 22:00

-----|------------------|---------|------------------|----->

16h 8h 16h

longer int. shorter int. longer int.Source: Created by the author.

Using the 12:00 hour as a threshold, it is possible to calculate the correct distance between times. This method links the values in a two-day timeline, where times equal to or greater than 12:00 are allocated to day 1, and times less than 12:00 are allocated to day 2. This ensures that the distance between 23:00 and 01:00 is calculated as 02:00, while the distance between 01:00 and 23:00 is 22:00, eliminating any gaps between data points. Figure B.7 illustrates this process.

Code

# library(dplyr)

# library(ggplot2)

# library(here)

# library(lubritime)

# library(patchwork)

# library(tidyr)

weighted_data <- targets::tar_read(

"weighted_data",

store = here::here("_targets")

)

plot_1 <-

weighted_data |>

dplyr::select(so_f) |>

tidyr::drop_na() |>

plotr:::plot_hist(

col = "so_f",

x_label = "Local time of sleep onset",

print = FALSE

)

plot_2 <-

weighted_data |>

dplyr::select(so_f) |>

dplyr::mutate(

so_f =

so_f |>

lubritime:::link_to_timeline(threshold = hms::parse_hms("12:00:00"))

) |>

tidyr::drop_na() |>

plotr:::plot_hist(

col = "so_f",

x_label = "Local time of sleep onset",

print = FALSE

)

patchwork::wrap_plots(

plot_1, plot_2,

ncol = 2

)Source: Created by the author.

Fortunately, the final values of the msf_sc variable (Chronotype proxy) in the analysis dataset were all after midnight, so no adjustments were required.

B.9.4 Round-Off Errors

The R programming language stores values with up to 53 binary digits of precision, equivalent to approximately \(15.955\) decimal digits (\(x = 53 \log_{10}(2)\)). Given that MCTQ primarily involves self-reported local times (e.g., 02:30) and durations (e.g., 15 minutes), this level of precision is more than sufficient. Even with multiple computations, round-off errors are unlikely to meaningfully affect the results.

Additionally, while POSIXct objects are used in the models, they provide ample precision. These objects represent date-time values as the number of seconds since the UNIX epoch (1970-01-01), ensuring accurate handling of time-related data.

B.10 Hypothesis Test

The study hypothesis was tested using nested multiple linear regressions. The primary concept of nested models is to evaluate the effect of adding one or more predictors on the model’s variance explanation (i.e., the \(\text{R}^{2}\)) (Allen, 1997; Maxwell et al., 2018). This is achieved by creating a restricted model (\(r\)) and comparing it with a full model (\(f\)).

To ensure practical significance, a Minimum Effect Size (MES) criterion was applied, in line with the original Neyman-Pearson framework for data testing (Neyman & Pearson, 1928a, 1928b; Perezgonzalez, 2015). The MES was set at a Cohen’s threshold for small effects (\(f^2 = 0.02\), equivalent to an \(\text{R}^2 = 0.01961\)) (“just barely escaping triviality” (Cohen, 1988, p. 413)). Consequently, latitude was considered meaningful only if its inclusion explained at least \(1.96078\%\) of the variance in the dependent variable.

The hypothesis can be outlined as follows:

- Null Hypothesis (\(\text{H}_{0}\))

- Including latitude as a predictor does not result in a meaningful improvement in the model’s fit, as evidenced by a change in the adjusted \(\text{R}^{2}\) that is less than the Minimum Effect Size (MES).

- Alternative Hypothesis (\(\text{H}_{a}\))

- Including latitude as a predictor results in a meaningful improvement in the model’s fit, as evidenced by a change in the adjusted \(\text{R}^{2}\) that meets or exceeds the Minimum Effect Size (MES).

Formally:

Conjecture B.1 (Data Test – Full Version) \[ \begin{cases} \text{H}_{0}: \Delta \ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} < \text{MES} \\ \text{H}_{a}: \Delta \ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} \geq \text{MES} \end{cases} \]

Where:

\[ \Delta \ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} = \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2}_{f} - \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2}_{r} \tag{B.1}\]

B.10.1 \(\text{R}^{2}\) and F-Test

\(\text{R}^{2}\) is a statistic that represents the proportion of variance explained in the relationship between two or more variables (goodness of fit) (Frey, 2022, p. 1339). It ranges from \(1\) (perfect prediction) to \(0\) (no prediction) and can be defined as (DeGroot & Schervish, 2012, p. 748):

\[ \text{R}^{2} = 1 - \cfrac{\text{SS}_{\text{residual}}}{\text{SS}_{\text{total}}} = 1 - \cfrac{\sum \limits^{n}_{i = 1} (y_{i} - \hat{y}_{i})^{2}}{\sum \limits^{n}_{i = 1} (y_{i} - \overline{y})^{2}} = \tag{B.2}\]

\[ = 1 - \cfrac{\text{Unexplained Variance}}{\text{Total Variance}} = \cfrac{\text{Explained Variance}}{\text{Total Variance}} \tag{B.3}\]

Where:

- \(y_{i}\) = Observed value of the dependent variable.

- \(\hat{y}_{i}\) = Predicted value of the dependent variable.

- \(\overline{y}\) = Mean of the dependent variable.

- \(\text{SS}_{\text{residual}}\) = Sum of the squared prediction errors (residuals) across all observations (DeGroot & Schervish, 2012, p. 748; Hair, 2019, p. 264).

- \(\text{SS}_{\text{total}}\) = Total sum of squares or the total amount of variation that exists to be explained by the independent variables. Is equivalent by the sum of the squared difference between the observed value and the mean of the dependent variable (baseline prediction) (DeGroot & Schervish, 2012, p. 748; Hair, 2019, p. 265).

The adjusted \(\text{R}^{2}\) is a modified version of \(\text{R}^{2}\) that adjusts for the number of predictors in the model. It can be defined as:

\[ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} = 1 - \cfrac{\text{SS}_{\text{residual}} / \text{df}_{\text{residual}}}{\text{SS}_{\text{total}} / \text{df}_{\text{total}}} = 1 - \cfrac{(1 - \text{R}^{2}) \times (\text{n} - 1)}{\text{n} - k - 1} \tag{B.4}\]

Where:

- \(\text{n}\) = Number of observations in the sample.

- \(k\) = Number of independent variables in the model.

- \(\text{df}_{\text{residual}}\) = Degrees of freedom of the residual sum of squares = \(n - k - 1\).

- \(\text{df}_{\text{total}}\) = Degrees of freedom of the total sum of squares = \(n - 1\).

The F-test serves as to determine wether the ratio of variances is different from zero (i.e., statistically significant) considering a baseline prediction (Hair, 2019, p. 300). In this case, the baseline prediction is the restricted model. The general equation for the F-test for nested models (Allen, 1997, p. 113) can be defined as:

\[ \text{F} = \cfrac{\text{R}^{2}_{f} - \text{R}^{2}_{r} / (k_{f} - k_{R})}{(1 - \text{R}^{2}_{f}) / (\text{n} - k_{f} - 1)} \tag{B.5}\]

Where:

- \(\text{R}^{2}_{f}\) = Coefficient of determination for the full model.

- \(\text{R}^{2}_{r}\) = Coefficient of determination for the restricted model.

- \(k_{f}\) = Number of independent variables in the full model.

- \(k_{r}\) = Number of independent variables in the restricted model.

- \(\text{n}\) = Number of observations in the sample.

\[ \text{F} = \cfrac{\text{Additional Var. Explained} / \text{Additional d.f. Expended}}{\text{Var. unexplained} / \text{d.f. Remaining}} \]

B.10.2 Minimum Effect Size (MES)

A MES must always be present in any data testing. The effect-size was present in the original Neyman and Pearson framework (Neyman & Pearson, 1928a, 1928b), but unfortunately this practice fade away with the indiscriminate use of \(p\)-values, one of the many issues that came with the Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST) (Perezgonzalez, 2015).

Neyman-Pearson’s approach considers, at least, two competing hypotheses, although it only tests data under one of them. The hypothesis which is the most important for the research (i.e., the one you do not want to reject too often) is the one tested (Neyman and Pearson, 1928; Neyman, 1942; Spielman, 1973). This hypothesis is better off written so as for incorporating the minimum expected effect size within its postulate (e.g., \(\text{HM} : \text{M1} – \text{M2} = 0 \pm \text{MES}\)), so that it is clear that values within such minimum threshold are considered reasonably probable under the main hypothesis, while values outside such minimum threshold are considered as more probable under the alternative hypothesis. (Perezgonzalez, 2015).

While \(p\)-values are estimates of type 1 error (in Neyman–Pearson’s approaches, or like-approaches), that’s not the main thing we are interested while doing a hypothesis test. What is really being test is the effect size (i.e., a practical significance). Another major issue to only relying on \(p\)-values is that the estimated \(p\)-value tends to decrease when the sample size is increased, hence, focusing just on \(p\)-values with large sample sizes results in the rejection of the null hypothesis, making it not meaningful in this specific situation (Gómez-de-Mariscal et al., 2021; Hair, 2019; Lin et al., 2013).

Although larger \(\text{R}^{2}\) values result in higher \(\text{F}\) values, the researcher must base any assessment of practical significance separate from statistical significance. Because statistical significance is really an assessment of the impact of sampling error, the researcher must be cautious of always assuming that statistically significant results are also practically significant. This caution is particularly relevant in the case of large samples where even small \(\text{R}^{2}\) values (e.g., \(5\%\) or \(10\%\)) can be statistically significant, but such levels of explanation would not be acceptable for further action on a practical basis. (Hair, 2019, p. 300)

Publications related to issues regarding the misuse of \(p\)-value are plenty. For more on the matter, see Perezgonzalez (2015) review of Fisher’s and Neyman-Pearson’s data test proposals, Lin et al. (2013) and Gómez-de-Mariscal et al. (2021) studies about large Samples and the \(p\)-value problem, and Cohen’s essays on the subject (like Cohen (1990) and Cohen (1994)).

It’s important to note that, in addition to the F-test, it’s assumed that for \(\text{R}^{2}_{\text{r}}\) to differ significantly from \(\text{R}^{2}_{\text{f}}\), there must be a non-negligible effect size between them. This effect size can be calculated using Cohen’s \(f^{2}\) (Cohen, 1988, 1992):

\[ \text{Cohen's } f^2 = \cfrac{\text{R}^{2}}{1 - \text{R}^{2}} \]

For nested models, this can be adapted as follows:

\[ \text{Cohen's } f^2 = \cfrac{\text{R}^{2}_{f} - \text{R}^{2}_{r}}{1 - \text{R}^{2}_{f}} = \cfrac{\Delta \text{R}^{2}}{1 - \text{R}^{2}_{f}} \]

\[ f^{2} = \cfrac{\text{Additional Var. Explained}}{\text{Var. unexplained}} \]

Given the significant role of the solar zeitgeber in the entrainment of biological rhythms, as evidenced by numerous studies, it is essential to ensure that the latitude hypothesis demonstrates at least a non-negligible effect size to be considered meaningful. To this end, Cohen’s threshold for small effects was applied, defining the Minimum Effect Size (MES) as \(f^2 = 0.02\) (Cohen, 1988, p. 413).

In Cohen’s words:

What is really intended by the invalid affirmation of a null hypothesis is not that the population ES [Effect Size] is literally zero, but rather that it is negligible, or trivial (Cohen, 1988, p. 16).

SMALL EFFECT SIZE: \(f^2 = .02\). Translated into ^{2} or partial ^{2} for Case 1, this gives \(.02 / (1 + .02) = .0196\). We thus define a small effect as one that accounts for 2% of the \(\text{Y}\) variance (in contrast with 1% for \(r\)), and translate to an \(\text{R} = \sqrt{0196} = .14\) (compared to .10 for \(r\)). This is a modest enough amount, just barely escaping triviality and (alas!) all too frequently in practice represents the true order of magnitude of the effect being tested (Cohen, 1988, p. 413).

[…] in many circumstances, all that is intended by “proving” the null hypothesis is that the ES is not necessarily zero but small enough to be negligible, i.e., no larger than \(i\). How large \(i\) is will vary with the substantive context. Assume, for example, that ES is expressed as \(f^2\), and that the context is such as to consider \(f^2\) no larger than \(.02\) to be negligible; thus \(i\) = .02 (Cohen, 1988, p. 461).

\[ \text{MES} = \text{Cohen's } f^2 \text{small threshold} = 0.02 \\ \]

For comparison, Cohen’s threshold for medium effects is \(0.15\), and for large effects is \(0.35\) (Cohen, 1988, pp. 413–414; 1992, p. 157).

Knowing Cohen’s \(f^2\), is possible to calculated the equivalent \(\text{R}^{2}\):

\[ 0.02 = \cfrac{\text{R}^{2}}{1 - \text{R}^{2}} \quad \text{or} \quad \text{R}^{2} = \cfrac{0.02}{1.02} \eqsim 0.01960784 \]

In other words, the latitude must explain at least \(1.96078\%\) of the variance in the dependent variable to be considered non-negligible.

The significance level (\(\alpha\)) was set at \(0.01\), allowing a 1% chance of a Type I error.

It’s important to emphasize that this thesis is not investigating causality, only association. Predictive models alone should never be used to infer causal relationships (Arif & MacNeil, 2022).

B.11 Statistical Analyses

In addition to the analyses described in the Hypothesis Test subsection, several other evaluations were conducted to ensure the validity of the results, including: a power analysis, the visual inspection of variable distributions (e.g., Q-Q plots), assessment of residual normality, checks for multicollinearity, and examination of leverage and influential points.

B.12 Model Predictors

Two modeling approaches were used to assess the impact of latitude and related environmental variables on the outcome of interest. Each approach builds on predictors inspired by the methods in Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017) while addressing methodological inconsistencies and data limitations (See Supplemantary Material L for more information).

B.12.1 Selection of Predictors

The restricted model in Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017) included age, longitude, and solar irradiation at the time of questionnaire completion as covariates, with sex, daylight saving time (DST), and season as cofactors. The full model added annual average solar irradiation, sunrise time, sunset time, and daylight duration for the March equinox and the June and December solstices. However, in this study:

- DST and season: Were excluded, as data collection occurred within a single week, making these variables redundant.

- Latitude proxies: Annual average solar irradiation and daylight duration for the March equinox and the June and December solstices were included. However, sunrise and sunset time coefficients were excluded due to high collinearity (\(r > 0.999\)). Attempts to resolve this issue through centralization or standardization of predictors were unsuccessful.

As in Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017), daylight duration for the September equinox was excluded due to its high correlation with the March equinox (\(r > 0.993\)), making it statistically indistinguishable (\(p > 0.05\)). This is expected, as the day length at the equinoxes is approximately equal (from the Latin aequĭnoctĭum, meaning “equal day and night” (Latinitium, n.d.)).

Daylight duration for the March equinox, June solstice, and December solstice exhibited high multicollinearity, with a variance inflation factor (VIF) exceeding \(1000\). However, since these variables belong to the same group, this does not pose a significant issue for the analysis. The focus is on the collective effect of the group rather than the individual contributions of each variable.

B.12.2 Tests

To evaluate the hypotheses, two tests were conducted using distinct sets of predictors. The first test replicated the approach from Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017), incorporating environmental proxies for latitude, while the second test directly included latitude as a predictor to assess its impact.

B.12.2.1 Test A

-

Restricted Model Predictors

- Age, sex, longitude, and monthly Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) corresponding to the participants’ geographic coordinates at the time of questionnaire completion.

-

Full Model Predictors

- Restricted model predictors + annual average GHI and daylight duration for the March equinox, June solstice, and December solstice, based on participants’ geographic coordinates.

B.12.2.2 Test B

-

Restricted Model Predictors

- Age, sex, longitude, and monthly Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) corresponding to the participants’ geographic coordinates at the time of questionnaire completion.

-

Full Model Predictors

- Restricted model predictors + latitude decimal degree based on participants’ geographic coordinates.