2 On Chronobiology

The dimension of time, manifest in the form of rhythms and cycles, such as the alternation of day and night and the annual transition of seasons, has consistently influenced the evolutionary trajectory of humans and all other life forms on our planet. These rhythms and cycles brought with them evolutionary pressures, resulting in the development of a temporal organization enabling organisms to survive and reproduce in response to the conditions imposed within their environments (Aschoff, 1989b; Paranjpe & Sharma, 2005; Pittendrigh, 1981, 1993). An example of this organization can be observed in the presence of different activity-rest patterns among living beings as they adapt to certain temporal niches, such as the diurnal behavior of humans and the crepuscular or nocturnal behavior of cats and certain rodents (Aschoff, 1989a; Kronfeld-Schor et al., 2017).

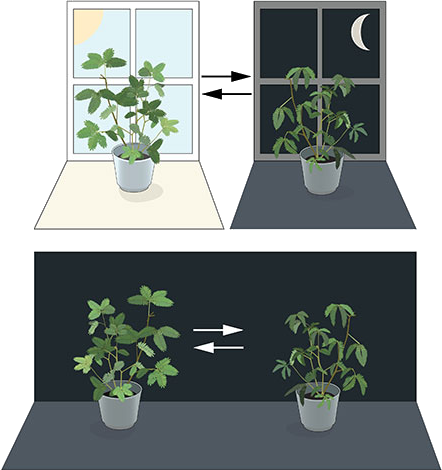

For years, scientists debated whether this organization was solely in response to environmental stimuli or if it was also present endogenously, internally, within organisms (Shackelford, 2022). One of the seminal studies describing a potential endogenous rhythmicity in living beings was conducted in 1729 by the French astronomer Jean Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan. De Mairan observed the movement of the sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica) by isolating it from the light/dark cycle and found that the plant continued to move its leaves periodically (Figure 2.1) (Mairan, 1729; Shackelford, 2022). The search for this internal timekeeper in living beings only began to solidify in the 20th century through the efforts of scientists like Jürgen Aschoff, Colin Pittendrigh, Franz Halberg, and Erwin Bünning, culminating in the establishment of the science known as chronobiology, with a significant milestone being the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology: Biological Clocks in 1960 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, n.d.; Shackelford, 2022)12. However, the recognition of endogenous rhythmicity by the global scientific community truly came in 2017 when Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael Young were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms that regulate the circadian rhythm3 in fruit flies (Nobel Prize Outreach AB, n.d.).

Source: Reproduced from Nobel Prize Outreach AB (n.d.).

Various biological rhythms have already been shown and described by science. These rhythms can occur at different description levels, whether at a higher level, such as the menstrual cycle (Ecochard et al., 2024), or even at a lower level, such as rhythms expressed within cells (Buhr & Takahashi, 2013; Sartor et al., 2023). Like many other biological phenomena, these are emergent properties of complex systems found in all living beings—stable macroscopic patterns arising from the collective behavior of the system’s parts, resulting in properties not attainable by the aggregate summation (Epstein, 1999; Holland, 2014). Today, it is understood that endogenous rhythms provide organisms with an anticipatory capacity, enabling them to preemptively organize resources and activities (Aschoff, 1989a).

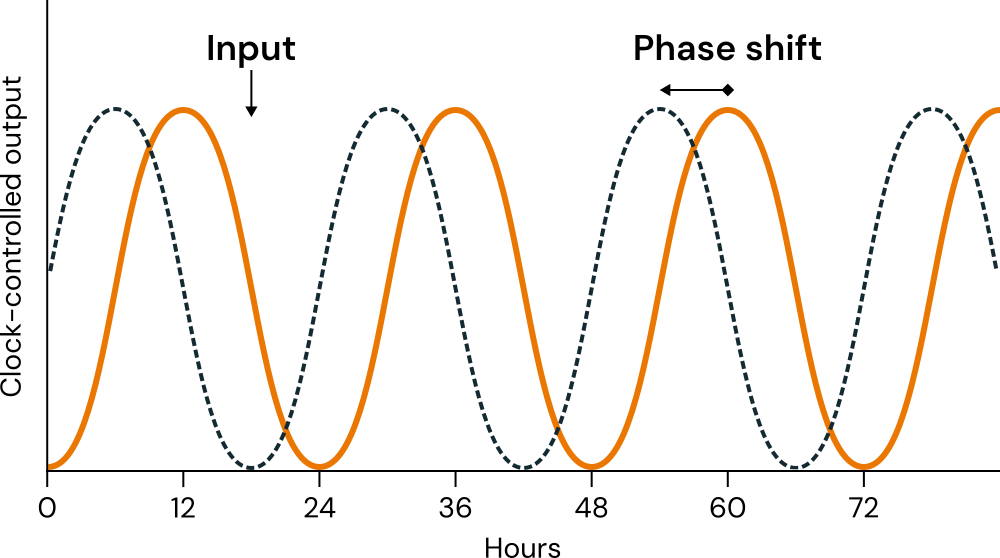

Despite the endogenous nature of these rhythms, they can still be regulated by the external environment. Signals (cues) from the environment that occur cyclically in nature and have the ability to regulate biological rhythmic expression are called zeitgebers4. These zeitgebers act as synchronizers by entraining the phases of the rhythms (Khalsa et al., 2003; Minors et al., 1991) (Figure 2.2). Among the known zeitgebers are, for example, meal timing (Flanagan et al., 2021) and changes in environmental temperature. However, the most influential of them is the light/dark cycle (or, simply, light exposure) (Aschoff, 1960; Pittendrigh, 1960; Roenneberg & Merrow, 2016). It is understood that the day/night cycle, resulting from the rotation of the Earth, has provided the vast majority of organisms with an oscillatory system with a periodic duration of approximately 24 hours (Aschoff, 1989a; Roenneberg, Kuehnle, et al., 2007).

Source: Adapted by the author from Kuhlman et al. (2018, Figure 2B).

The expression of this temporal organization varies among organisms, even within the same species (Duffy et al. (2011); Silvério et al. (2024)). These variations can be attributed to differences in how organisms experience their environment or to differences in their endogenous rhythmicity, a characteristic ultimately influenced by gene expression (Roenneberg, Kumar, et al., 2007). The interplay between environmental influences and genetic predisposition results in an observable characteristic: the phenotype (Frommlet et al., 2016).

The various temporal characteristics of an organism can be linked to different oscillatory periods. Among these are circadian phenotypes, which refer to characteristics observed in rhythms with periods lasting about a day (Foster & Kreitzman, 2005). Another term used for these temporal phenotypes, as the name suggests, is chronotype (Ehret, 1974; Pittendrigh, 1993). This term is also often used to differentiate phenotypes on a spectrum ranging from morningness to eveningness (Horne & Östberg, 1976; Roenneberg et al., 2019).

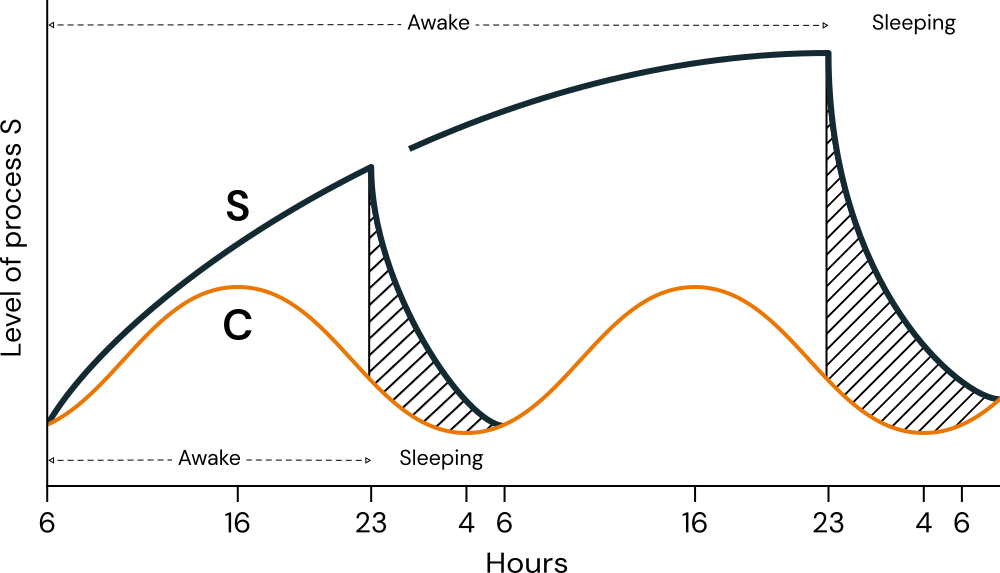

Sleep is a phenomenon that exhibits circadian expression. By observing the sleep characteristics of individuals, it is possible to assess the distribution of circadian phenotypes within a population, thereby investigating their covariates and other relevant associations (Roenneberg et al., 2003). This is because sleep is understood to result from the interaction of two processes: a homeostatic process (The \(\text{S}\) process), which is sleep-dependent and accumulates with sleep deprivation, and a circadian process (The \(\text{C}\) process), whose expression can be influenced by zeitgebers such as the light/dark cycle (Borbély, 1982; Borbély et al., 2016). These two processes are illustrated in Figure 2.3. Because the circadian rhythm is a component of sleep, its characteristics can be inferred by isolating its effects from those of the \(\text{S}\) process.

The figure depicts two scenarios: One with \(17\) hours of wakefulness followed by \(7\) hours of sleep; and another, under sleep deprivation, with \(41\) hours of wakefulness followed by \(7\) hours of sleep. The hatched areas indicate periods of sleep, illustrating the exponential decline of Process \(\text{S}\).

Source: Adapted by the author from Borbély (1982, Figure 4).

Building on this idea, Roenneberg et al. (2003) developed the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) to measure the circadian phenotype through sleep patterns. The MCTQ asks individuals about their sleep habits, such as the times they go to bed and wake up on workdays and work-free days. From this information, the MCTQ derives the midpoint of sleep on work-free days, representing the average of sleep onset and offset times (Figure 2.4). If sleep deprivation is detected on workdays, the scale adjusts the measurement accordingly. This midpoint, reflecting sleep under minimal social constraints, is considered a closer approximation of the intrinsic circadian rhythm and, therefore, a useful proxy for estimating the circadian phenotype (the \(\text{C}\) process) (Leocadio-Miguel et al., 2014).

BT = Local time of going to bed. SPrep = Local time of preparing to sleep. SLat = Sleep latency (Duration. Time to fall asleep after preparing to sleep). SO = Local time of sleep onset. SD = Sleep duration. MS = Local time of mid-sleep. SE = Local time of sleep end. Alarm = Indicates whether the respondent uses an alarm clock. SI = “Sleep inertia” (Duration. Despite the name, this variable represents the time the respondent takes to get up after sleep end). GU = Local time of getting out of bed. TBT = Total time in bed.

Source: Created by the author.

The MCTQ facilitates the evaluation of chronotype in population studies. This thesis employs the MCTQ to assess chronotype using data from a 2017 online survey conducted by the author, which includes responses from \(65,824\) Brazilians and geographical information such as postal codes. This dataset enables the investigation of potential associations between chronotype and geographic factors.

Some say the term chronobiology was coined by Franz Halberg during the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium (Menna-Barreto & Marques, 2023, p. 21).↩︎

From the Greek chrónos, meaning time/duration, and biology, pertaining to the study of life (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).↩︎

From the Latin circā, meaning around, and dĭes, meaning day (Latinitium, n.d.)—a rhythm with an approximately 24-hour period.↩︎

From the German zeit, meaning time, and geber, meaning donor (Cambridge University Press, n.d.).↩︎