5 Is Latitude Associated with Chronotype?

The following study was designed for publication in the journal Scientific Reports (IF 2023: 3.8/JCR | CAPES: A1/2017–2020) and structured in accordance with the journal’s submission guidelines.

5.1 Abstract

Chronotypes are temporal phenotypes that reflect our internal temporal organization, a product of evolutionary pressures enabling organisms to anticipate events. These intrinsic rhythms are entrain by zeitgebers—periodical environmental stimuli with the ability to regulate biological rhythmic expression, with light exposure being the primary mechanism. Given light’s role in these systems, previous research hypothesized that latitude might significantly influence chronotypes, suggesting that populations near the equator would exhibit more morning-leaning characteristics due to more consistent light/dark cycles, while populations near the poles might display more evening-leaning tendencies with a potentially freer expression of intrinsic rhythms. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed chronotype data from a large sample of \(65,824\) subjects across diverse latitudes in Brazil. Our results revealed a negligible effect size of latitude on chronotype (\(f^2 = 0.00314, 95\% \ \text{CI}[0, 0.0122]\)), indicating that the entrainment phenomenon is far more complex than previously conceived. These findings challenge simplified environmental models of biological timing and underscore the need for more nuanced investigations into the mechanisms underlying temporal phenotypes, opening new avenues for understanding the intricate relationship between environmental cues and individual circadian rhythms.

5.2 Introduction

Humans exhibit a variety of observable traits, such as eye or hair color, which are referred to as phenotypes. These phenotypes also manifest in the way our bodies function.

A chronotype is a temporal phenotype (Ehret, 1974; Pittendrigh, 1993), often used to describe endogenous circadian rhythms—biological rhythms with periods close to 24 hours. Chronobiology, the field dedicated to studying biological rhythms, posits that the evolution of these internal oscillators is intricately tied to environmental factors, particularly the day/night cycle. This cycle, in conjunction with human evolution, is believed to have exerted selective pressures that fostered the development of temporal organization within organisms (Aschoff, 1989b; Paranjpe & Sharma, 2005; Pittendrigh, 1981). Such organization enables organisms to anticipate environmental changes and optimize survival strategies, such as storing food for winter (Aschoff, 1989a).

For a temporal system to be effective, it must adapt to environmental changes. Environmental cues that regulate biological rhythms are termed zeitgebers (from the German zeit, meaning time, and geber, meaning giver (Cambridge University Press, n.d.)). These zeitgebers act as inputs that shift and synchronize biological rhythms through a process known as entrainment (Khalsa et al., 2003; Minors et al., 1991).

The primary zeitgeber influencing biological rhythms is the light/dark cycle, or, simply, light exposure (Aschoff, 1960; Pittendrigh, 1960; Roenneberg & Merrow, 2016). Given its significant role in entraining the biological clock, several studies have hypothesized that the latitudinal shift of the sun, due to the Earth’s axial tilt, might lead to different temporal traits in populations near the equator compared to those closer to the poles (Bohlen & Simpson, 1973; Horzum et al., 2015; Leocadio-Miguel et al., 2014, 2017; Randler, 2008). This is based on the idea that populations at low or higher latitudes experience greater fluctuations in sunlight and a weaker overall solar zeitgeber. This concept is known as the latitude hypothesis, or the environmental hypothesis of circadian rhythm regulation.

Several studies have claimed to find this association in humans, but the evidence they provide is of very low quality or simply misleading (Horzum et al., 2015; Leocadio-Miguel et al., 2014, 2017; e.g., Randler, 2008; Wang et al., 2023). A notable attempt was made by Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017), who measured the chronotype of \(12,884\) Brazilian subjects across a wide latitudinal range using the Horne-Östberg (HO) Morningness–Eveningness questionnaire (Horne & Östberg, 1976). Although the authors concluded that there was a meaningful association between latitude and chronotype, their results were too small to be considered practically significant (even by lenient standards), with latitude explaining only approximately \(0.388\%\) of the variance in chronotype (Cohen’s \(f^2 = 0.00414\)). One possible explanation for this result is that the HO measures psychological traits rather than the biological states of circadian rhythms themselves (Roenneberg, Pilz, et al., 2019), suggesting it may not be the most suitable tool for testing the hypothesis (Leocadio-Miguel et al., 2014).

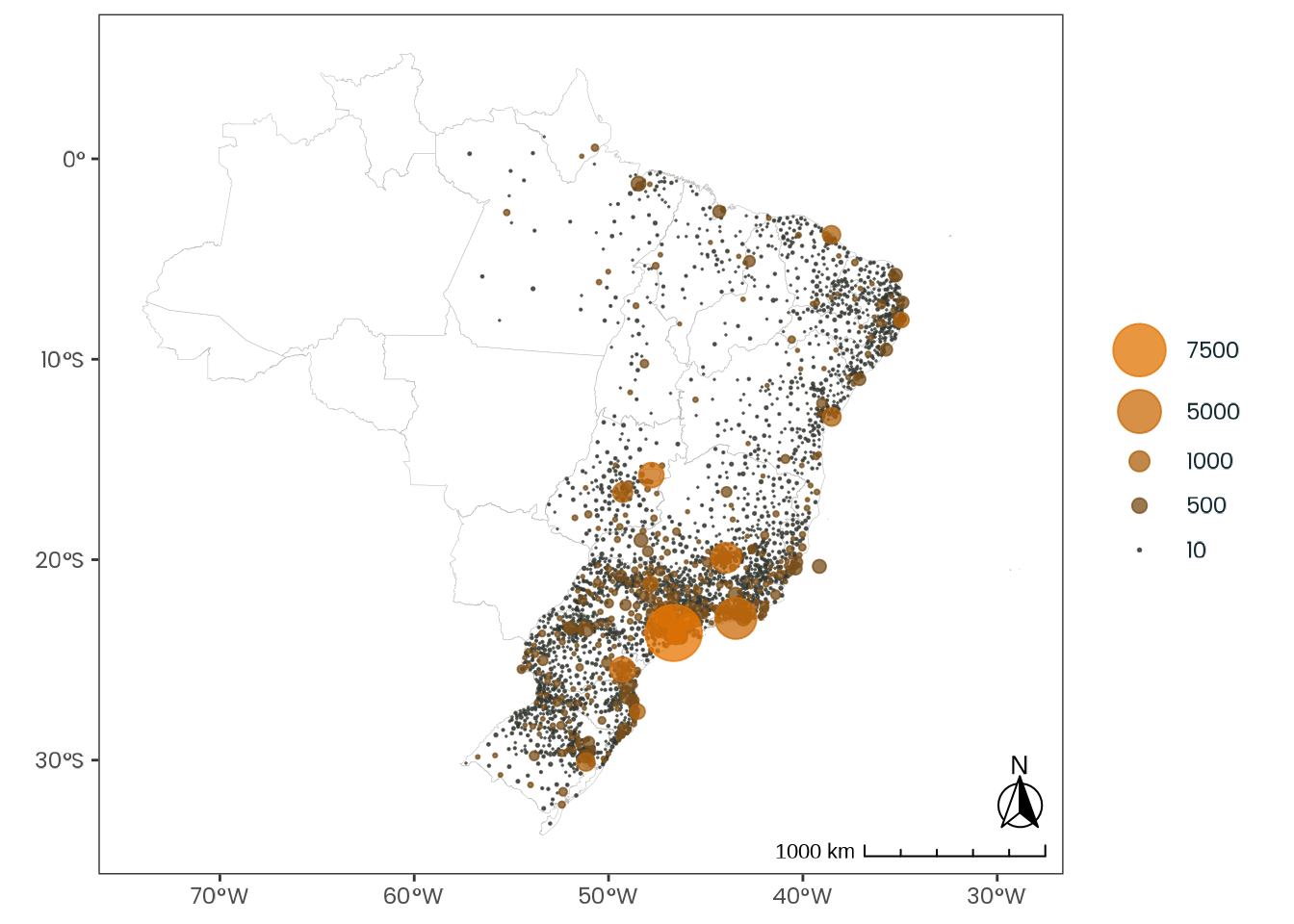

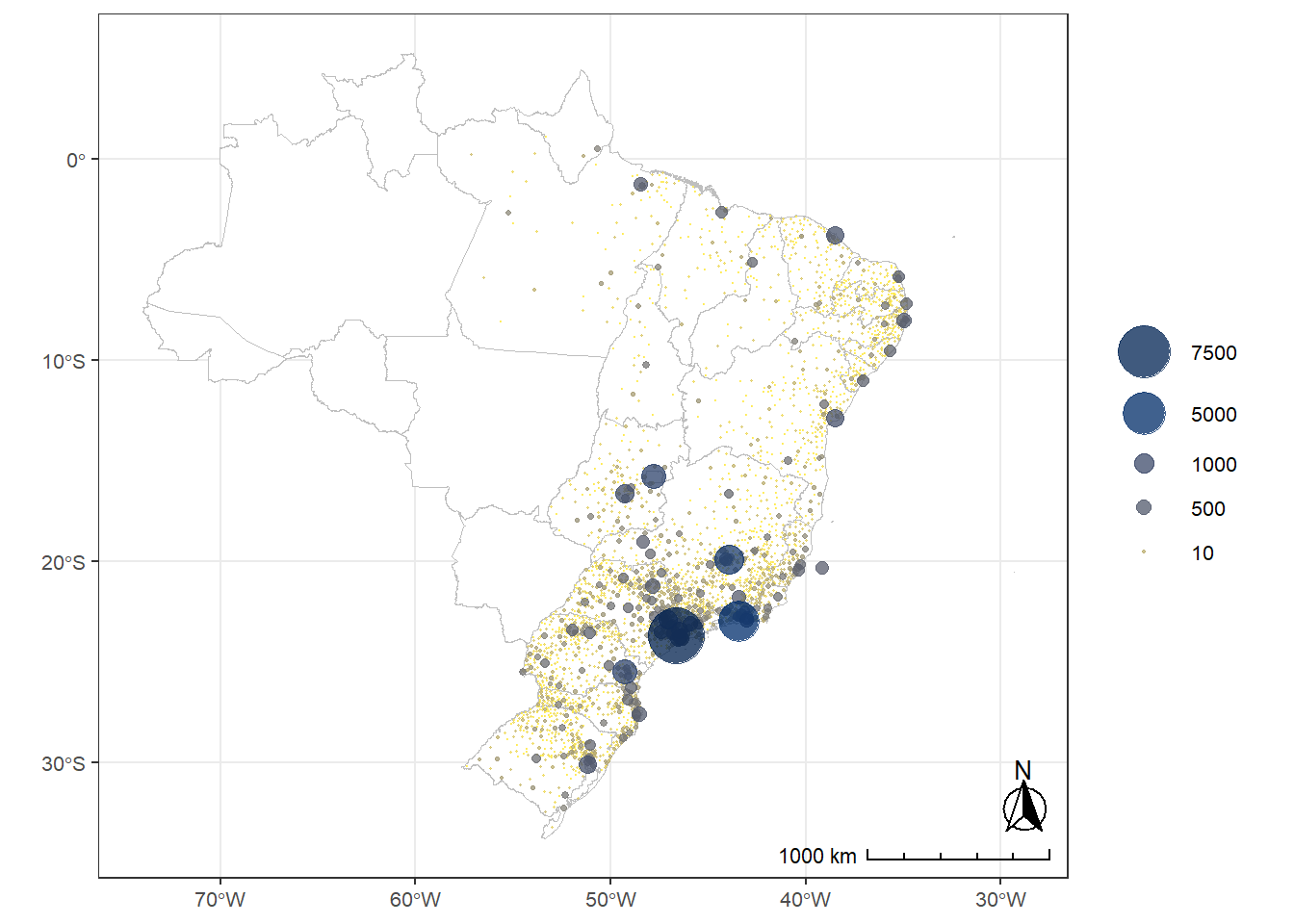

Building on Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017), this study offers a novel attempt to test the latitude hypothesis by employing a biological approach through the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ) (Roenneberg et al., 2003) and an enhanced statistical methodology. Additionally, it utilizes the largest dataset on chronotype from a single country, as far as the existing literature suggests, comprising \(65,824\) respondents, all residing within the same timezone in Brazil and completing the survey within a one-week window (Figure 5.1).

Code

weighted_data |>

plotr:::plot_brazil_municipality(

year = 2017,

transform = "log10",

direction = -1,

alpha = 0.75,

breaks = c(10, 500, 1000, 5000, 7500),

point = TRUE

)Each point represents a municipality, with its size proportional to the number of participants and color intensity increasing with participant count. The sample includes Brazilian individuals aged 18 or older, residing in the UTC-3 timezone, who completed the survey between October 15th and 21st, 2017. The size and color scale are logarithmic.

Source: Created by the author.

5.3 Results

The Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ) uses the midpoint between sleep onset (SO) and sleep end (SE) on work-free days (MSFsc), with a sleep correction (sc) applied if sleep debt is detected, as a proxy for chronotype (Roenneberg et al., 2003). For example, if an individual sleeps from \(\text{00:00}\) to \(\text{08:00}\), the midpoint would be \(\text{04:00}\). This measure is based on the current understanding of sleep regulation, which comprises a homeostatic/sleep-dependent process (\(\text{S}\) process) and a circadian process (\(\text{C}\) process) (Borbély, 1982; Borbély et al., 2016). The midpoint of sleep on free days offers a way to observe unrestrained sleep behavior, thereby minimizing the influence of the \(\text{S}\) process and providing a better approximation of the circadian phenotype (i.e., the \(\text{C}\) process).

Our analysis revealed an overall mean MSFsc of \(\text{04:28:41}\), with an standard deviation of \(\text{01:26:13}\). The distribution is shown in Figure 5.2.

Code

weighted_data |> plotr:::plot_chronotype()Chronotypes are categorized into quantiles, ranging from extremely early (\(0 |- 0.111\)) to extremely late (\(0.888 |- 1\)).

Source: Created by the author based on a data visualization from

Roenneberg, Wirz-Justice, et al. (2019, Figure 1).

This represents the midsleep point for Brazilian subjects living in the UTC-3 timezone, with an intermediate or average chronotype. Considering the \(7–9\) hours of sleep recommended for healthy adults by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) (Watson et al., 2015), one might infer that this average individual, in the absence of social constraints, would typically wake up at approximately \(\text{08:28:41}\).

The study hypothesis was tested using nested multiple regressions, based on the design of the models presented in Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017). The core idea of nested models is to evaluate the effect of including one or more predictors on the model’s variance explanation (\(\text{R}^2\)) (Maxwell et al., 2018). This is achieved by comparing a restricted model (without the latitude) with a full model (with the latitude). Cell weights, based on sex, age group, and state of residence, were applied to account for sample imbalances.

To ensure practical significance, the hypothesis test incorporated a minimum effect size (MES) criterion, consistent with the original Neyman-Pearson framework for data testing (Neyman & Pearson, 1928a, 1928b; Perezgonzalez, 2015). The MES was set at Cohen’s \(f^2\) of \(0.02\) (equivalent to an \(\text{R}^2\) of \(0.01961\)), a lenient threshold (Cohen, 1988). Given the established role of solar zeitgebers in biological rhythm entrainment, it would be unreasonable to support the latitude hypothesis without demonstrating at least a non-trivial effect size.

Two tests were conducted, both starting with the same restricted model, which included age, sex, longitude, and the average monthly Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) at the time of questionnaire completion as predictors (\(\text{R}^2_{\text{adj}} = 0.08517\), \(\text{F}(4, 65818) = 1531.829\), \(p\text{-value} < 1e-05\)).

The first full model (A) added the average annual GHI and daylight duration for the nearest March equinox, as well as the June and December solstices, as proxies for latitude, following the methods of Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017) (\(\text{R}^2_{\text{adj}} = 0.08803\), \(\text{F}(8, 65814) = 794.119\), \(p\text{-value} < 1e-05\)).

The second full model (B) included only latitude as an additional predictor (\(\text{R}^2_{\text{adj}} = 0.08568\), \(\text{F}(5, 65817) = 1233.601\), \(p\text{-value} < 1e-05\)).

All coefficients were statistically significant (\(p\text{-value} < 0.05\)). Assumption checking and residual diagnostics were primarily conducted through visual inspection, as formal assumption tests (e.g., Anderson-Darling) are often not recommended for large samples (Shatz, 2024). All validity assumptions were satisfied, and no significant multicollinearity was detected among the predictor variables.

An ANOVA for nested models revealed a significant reduction in the residual sum of squares in both tests (A, \(\text{F}(4, 65814) = 51.691\), \(p\text{-value} < 1e-05\)) (B, \(\text{F}(1, 65817) = 37.312\), \(p\text{-value} < 1e-05\)). However, similarly to Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017), when estimating Cohen’s \(f^2\) effect size, the results were below the MES (i.e., negligible) (A, \(f^2 = 0.00314, 95\% \ \text{CI}[0, 0.0122]\)) (B, \(f^2 = 0.00057, 95\% \ \text{CI}[0, 0.00954]\)).

5.4 Discussion

We emphasize that the assumption of a causal, linear relationship between latitude and chronotype constitutes an a priori hypothesis, which this study seeks to falsify.

Despite a broad latitudinal range (\(33.85\) degrees) and a large, balanced sample, our results indicate that the effect of latitude on chronotype is negligible. Indeed, despite suggestions of a potential link in several studies, robust empirical evidence supporting this claim in humans is lacking.

Our results align with those of Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017), who reported a similar effect size (Cohen’s \(f^2 = 0.00414\)). However, their analysis did not incorporate a minimum effect size criterion, leading to misleading interpretations.

The small and inconsistent nature of the latitude effect is illustrated in Figure 5.3, while Figure 5.4 displays the mean chronotype by Brazilian state. The distribution of chronotypes across latitudes is further illustrated in Figure 5.5.

Code

weighted_data |> plotr:::plot_latitude_series()MSFsc is a proxy for chronotype, representing the midpoint of sleep on work-free days, adjusted for sleep debt. Higher MSFsc values indicate a tendency towards eveningness. The × symbol points to the mean. The orange line represents a linear regression. The differences in mean/median values across latitudes are minimal relative to the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ) scale.

Source: Created by the author.

The absence of a clear relationship between latitude and chronotype can be attributed to multiple factors. As Jürgen Aschoff might have put it, this may reflect a lack of “ecological significance” (Aschoff et al., 1972, p. 277). Even if latitude does influence circadian rhythms, the effect might be overshadowed by other, more prominent factors like social behaviors, work hours, or the widespread use of artificial lighting. Furthermore, the variations in sunlight exposure between latitudes may not be substantial enough to meaningfully impact the circadian system, which is highly responsive to light. Given that even minor light fluctuations can lead to measurable physiological changes (Khalsa et al., 2003; Minors et al., 1991), latitude alone may not be a decisive factor in determining chronotype.

Code

limits <- # Interquartile range (IQR): Q3 - Q1

c(

weighted_data |>

dplyr::pull(msf_sc) |>

lubritime::link_to_timeline() |>

as.numeric() |>

stats::quantile(0.25, na.rm = TRUE),

weighted_data |>

dplyr::pull(msf_sc) |>

lubritime::link_to_timeline() |>

as.numeric() |>

stats::quantile(0.75, na.rm = TRUE)

)

weighted_data |>

dplyr::mutate(

msf_sc =

msf_sc |>

lubritime:::link_to_timeline() |>

as.numeric()

) |>

plotr:::plot_brazil_state(

col_fill = "msf_sc",

year = 2017,

scale_type = "continuous",

breaks =

seq(limits[1], limits[2], length.out = 6) |>

groomr::remove_caps(),

labels = plotr:::format_as_hm,

limits = limits, # !!!

quiet = TRUE,

reverse = TRUE

)MSFsc is a proxy for chronotype, representing the midpoint of sleep on work-free days, adjusted for sleep debt. Higher MSFsc values indicate a tendency towards eveningness. The color scale is bounded by the first and third quartiles. Differences in mean MSFsc values across states are small and fall within a narrow range relative to the scale of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ), limiting the significance of these variations.

Source: Created by the author.

The results highlight the complex nature of the human chronotype and emphasize the importance of investigating alternative factors that may influence them. The perceived link between these variables may be a consequence of prioritizing statistical rituals over statistical thinking and a tendency toward confirmation bias, rather than rigorous and unbiased data analysis.

Code

plot <-

weighted_data |>

dplyr::mutate(

msf_sc_category = plotr:::categorize_msf_sc(msf_sc),

msf_sc_category = factor(

msf_sc_category,

levels = c(

"Extremely early", "Moderately early", "Slightly early",

"Intermediate", "Slightly late", "Moderately late",

"Extremely late"

),

ordered = TRUE

)

) |>

plotr:::plot_brazil_point(

col_group = "msf_sc_category",

year = 2017,

size = 0.1,

alpha = 1,

print = FALSE,

scale_type = "d"

) +

ggplot2::theme(

axis.title = ggplot2::element_blank(),

axis.text= ggplot2::element_blank(),

axis.ticks = ggplot2::element_blank(),

panel.grid.major = ggplot2::element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor = ggplot2::element_blank(),

legend.position = "none"

)

plot |>

plotr:::rm_ggspatial_scale() +

ggplot2::facet_wrap(~msf_sc_category, ncol = 4, nrow = 2)MSFsc is a proxy for chronotype, representing the midpoint of sleep on work-free days, adjusted for sleep debt. Chronotypes are categorized into quantiles, ranging from extremely early (\(0 |- 0.111\)) to extremely late (\(0.888 |- 1\)). No discernible pattern emerges from the distribution of chronotypes across latitudes.

Source: Created by the author.

While this study does not outright refute the hypothesis, the association between latitude and chronotype should remain an open scientific question rather than be treated as established knowledge until supported by robust evidence.

5.5 Methods

5.5.1 Measurement Instrument

Chronotypes were assessed using a standard version of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire (MCTQ) (Roenneberg et al., 2003), a well-validated and widely used self-report tool for measuring sleep-wake behavior and determining chronotype (Roenneberg, Pilz, et al., 2019). The MCTQ derives chronotype from the sleep-corrected midpoint of sleep on free days (MSFsc), which compensates for sleep debt incurred during the workweek (Roenneberg, 2012). Figure 5.6 illustrates the variables collected by the MCTQ.

BT = Local time of going to bed. SPrep = Local time of preparing to sleep. SLat = Sleep latency (Duration. Time to fall asleep after preparing to sleep). SO = Local time of sleep onset. SD = Sleep duration. MS = Local time of mid-sleep. SE = Local time of sleep end. Alarm = Indicates whether the respondent uses an alarm clock. SI = “Sleep inertia” (Duration. Despite the name, this variable represents the time the respondent takes to get up after sleep end). GU = Local time of getting out of bed. TBT = Total time in bed.

Source: Created by the author.

Participants completed an online questionnaire, which included the MCTQ as well as sociodemographic (e.g., age, sex), geographic (e.g., full residential address), anthropometric (e.g., weight, height), and data on work and study routines. A version of the questionnaire, stored independently by the Internet Archive organization, can be viewed at: https://web.archive.org/web/20171018043514/each.usp.br/gipso/mctq

5.5.2 Sample Characteristics

The analysis dataset consisted of \(65,824\) participants aged 18 or older residing in the UTC-3 timezone. These individuals completed the survey during a one-week period from October 15th to 21st, 2017, providing a snapshot of the population at that specific time.

The unfiltered valid sample included \(115,166\) participants from all Brazilian states. The raw dataset contained \(120,265\) individuals, with \(98.173\%\) of the responses collected between October 15th and 21st, 2017. This data collection period coincided with the promotion of the online questionnaire via a broadcast on a nationally televised Sunday show in Brazil (Rede Globo, 2017).

Based on 2017 data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’s (IBGE) Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNAD Contínua) (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, n.d.), Brazil had \(51.919\%\) of females and \(48.081\%\) of males with an age equal to or greater than 18 years old. The sample is skewed for female subjects, with \(66.433\%\) of females and \(33.567\%\) of male subjects. The mean age was \(32.109\) (\(\text{SD} = 9.258\)), ranging from \(18\) to \(58.95\) years.

To balance the sample, weights were incorporated into the models. These weights were calculated through cell weighting, using sex, age group, and state of residence as references, based on population estimates from IBGE for the same year as the sample.

A survey conducted in 2019 by IBGE (2021) found that \(82.17\%\) of Brazilian households had access to an internet connection. Therefore, this sample is likely to have a good representation of Brazil’s population.

The sample latitudinal range is \(33.85°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -33.522°\), \(\text{Max.} = 0.329°\)) with a longitudinal span of \(22.741°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -57.553°\), \(\text{Max.} = -34.812°\)). For comparison, Brazil has a latitudinal range of \(39.023°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -33.751°\); \(\text{Max.} = 5.272°\)) and a longitudinal span of \(45.155°\) (\(\text{Min.} = -73.99°\); \(\text{Max.} = -28.836°\)), according to data from IBGE collected via the geobr R package (R. H. M. Pereira & Goncalves, n.d.).

Additional details about the sample are available in the supplementary materials.

5.5.3 Power Analysis

To assess the adequacy of the sample size for detecting effects reaching the Minimum Effect Size (MES) threshold (\(f^2 = 0.02\)), we conducted a power analysis using the pwrss R package (Bulus, n.d.). This analysis revealed a minimum sample size of \(1,895\) observations per variable to achieve a power (\(1 - \beta\)) of \(0.99\) with a significance level (\(\alpha\)) of \(0.01\). Our sample size (\(n = 65,824\)) comfortably surpasses this threshold, ensuring adequate power.

5.5.4 Geographical Data

We obtained latitude and longitude data by geocoding participants’ residential addresses using two main resources:

- QualoCEP (Qual o CEP, 2024): A dataset of Brazilian postal codes with integrated geocoding via the Google Geocoding API. This served as our primary source.

- Google Geocoding API: Used for addresses not included in QualoCEP. We employed the tidygeocoder R package (Cambon et al., 2021) to facilitate this process.

To ensure consistency, we randomly compared results from QualoCEP and Google Geocoding API. This can be seen in the supplementary materials.

5.5.5 Solar Irradiance Data

The solar irradiance data came from the 2017 Solar Energy Atlas of Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) (E. B. Pereira et al., 2017). We used the Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) data, representing the total amount of irradiance received from above by a surface horizontal to the ground.

5.5.6 Astronomical Calculations

The suntools R package (Bivand & Luque, n.d.) was employed to calculate sunrise, sunset times, and daylight duration for each participant’s location. These calculations are based on equations provided by Meeus (1991) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The dates and times of equinoxes and solstices were acquired from the Time and Date AS service (Time and Date AS, n.d.). To verify accuracy, we compared this data with the equations from Meeus (1991) and the results from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) ModelE AR5 Simulations (National Aeronautics and Space Administration & Goddard Institute for Space Studies, n.d.).

5.5.7 Data Munging

Data munging and analysis followed the data science framework proposed by Hadley Wickham and Garrett Grolemund (Wickham et al., 2023). All processes were conducted using the R programming language (R Core Team, n.d.) and several R packages. The tidyverse and rOpenSci peer-reviewed package ecosystem and other R packages adherents of the tidy tools manifesto (Wickham, 2023) were prioritized.

The MCTQ data was analyzed using the mctq R package (Vartanian, n.d.), which is part of the rOpenSci peer-reviewed ecosystem. The data pipeline was built using the rOpenSci peer-reviewed targets R package (Landau, 2021), which provides a reproducible and efficient workflow for data analysis.

All processes were designed to ensure result reproducibility and adherence to the FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) (Wilkinson et al., 2016). All analyses are fully reproducible and were conducted using Quarto computational notebooks. The renv R package (Ushey & Wickham, n.d.) was employed to ensure that the R analysis environment can be reliably restored.

5.5.8 Hypothesis Test

To test the study hypothesis, nested multiple linear regression models were compared: a restricted model (excluding latitude) and a full model (including latitude). The restricted model included sex, age, longitude, and the average monthly Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) at the time of questionnaire completion related to the latitude/longitude of each respondent as predictors.

Two full models were tested. The first model (A) included the restricted predictors along with proxies for latitude, such as the average annual GHI and daylight duration for the nearest March equinox, as well as the June and December solstices. These proxies were derived based on the latitude and longitude of each respondent. The second model (B) included the restricted predictors with latitude (in decimal degrees) as the sole additional predictor. It is important to notice that the design of the models were based on Leocadio-Miguel et al. (2017) study.

Cell weights were applied to account for sample imbalances. The models were compared using an F-test for nested models, considering a Type I error probability (\(\alpha\)) of \(0.05\).

To ensure practical significance, a Minimum Effect Size (MES) criterion was applied, in line with the original Neyman-Pearson framework for data testing (Neyman & Pearson, 1928a, 1928b; Perezgonzalez, 2015). The MES was set at a Cohen’s threshold for small effects (\(f^2 = 0.02\), equivalent to an \(\text{R}^2 = 0.01961\)) (“just barely escaping triviality” (Cohen, 1988, p. 413)). Consequently, latitude was considered meaningful only if its inclusion explained at least \(1.96078\%\) of the variance in the dependent variable.

The hypothesis can be outlined as follows:

- Null Hypothesis (\(\text{H}_{0}\))

- Including latitude as a predictor does not result in a meaningful improvement in the model’s fit, as evidenced by a change in the adjusted \(\text{R}^{2}\) that is less than the Minimum Effect Size (MES).

- Alternative Hypothesis (\(\text{H}_{a}\))

- Including latitude as a predictor results in a meaningful improvement in the model’s fit, as evidenced by a change in the adjusted \(\text{R}^{2}\) that meets or exceeds the Minimum Effect Size (MES).

Formally:

\[ \begin{cases} \text{H}_{0}: \Delta \ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} < \text{MES} \\ \text{H}_{a}: \Delta \ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} \geq \text{MES} \end{cases} \]

Where:

\[ \Delta \ \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2} = \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2}_{\text{full}} - \text{Adjusted} \ \text{R}^{2}_{\text{restricted}} \]

5.6 Data Availability

Some restrictions apply to the availability of the main research data, which contain personal and sensitive information. As a result, this data cannot be publicly shared. Data are, however, available from the author upon reasonable request.

The code repository is available on GitHub at https://github.com/danielvartan/mastersthesis, and the research compendium can be accessed via The Open Science Framework at the following link: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YGKTS

5.7 Acknowledgments

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001, Grant number 88887.703720/2022-00.

5.8 Ethics Declaration

The author declares that the study was carried out without any commercial or financial connections that could be seen as a possible competing interest.

5.9 Additional Information

See the supplementary material for more information.

Correspondence can be sent to Daniel Vartanian (danvartan@gmail.com).

5.10 Rights and Permissions

This article is released under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as be given appropriate credit to the original author and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.